Friends, We Have a Hero Problem

Le Guin, Potatoes, & why it's time to give heroes the boot

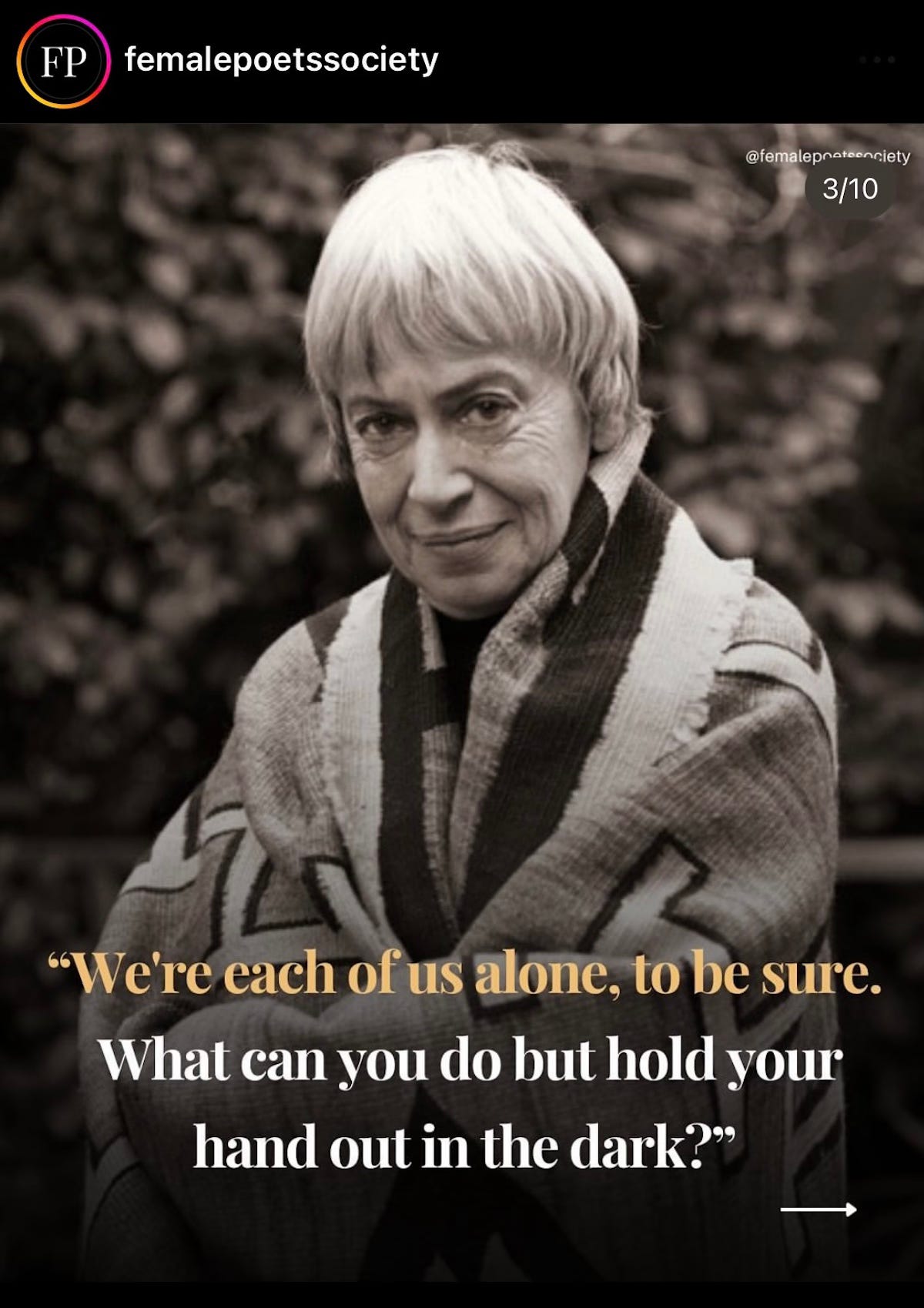

I turned in my thesis for grad school earlier this week, and I’ve been prepping to teach a class at my upcoming last residency this winter(!!). The class is called “Carrier Bags & Bright Containers: Structuring a Collection.” While working on this class, I have returned to the iconic essay by Ursula K Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” (If you haven’t read it before, it’s not that long, go ahead, I’ll wait right here.)

This essay is one I come back to as a writer, but more importantly, it’s an essay that also shapes how I understand the world and what is happening around me. Le Guin wrote this essay in 1986, but it is just as relevant now, as we watch our fellow citizens, with whom we should theoretically be united in our common desires for well-being, sustenance, and safety—but instead, we regard each other with fear, revulsion, anger, and suspicion.

We have a serious problem with heroes, and with the stories we tell about heroes.

All people everywhere are shaped by the stories in their culture. All cultures make meaning through narrative, and pass down that meaning to the next generations through stories. These stories do change, it’s true, and also, here we are in the West still telling stories we inherited from the ancient Greeks, from the Romans, from the Bible, from the Puritans. We keep these stories alive and tell them as though they are true. We tell them as though they are correct and, as though they are lighthouses to guide our own decisions. And indeed, they do just that.

In her essay, Le Guin argues that we hold a common belief that the hero is the center of any story. He—it is usually a he—deserves to be at the center. And that we believe there is no story worth telling that does not have a hero, with conflict at its center—conflict is what makes the story go. (Side note: this is not true in all cultures or all storytelling traditions, but it is quite common, and is definitely rampant in US/European traditions.)

“It is the [hero] story that makes the difference,” Le Guin writes, “It is the story that hid my humanity from me, the story the mammoth hunters told about bashing, thrusting, raping, killing, about the Hero…The trouble is, we've all let ourselves become part of the killer story, and so we may get finished along with it. Hence it is with a certain feeling of urgency that I seek the nature, subject, words of the other story, the untold one, the life story.”

While heroes may have hijacked our storytelling, to the extent that we can hardly even conceive of how to write or tell a story without one, Le Guin argues that the natural shape of a story is a bag. A carrier bag, the first human tool (as proposed by anthropologist Elizabeth Fisher, whom Le Guin’s essay is in conversation with). Not a weapon, as is often argued. Le Guin calls for us to return to the container story, to write about people instead of heroes.

So…what does all of this have to do with you, and with me? It has to do with how we see ourselves in the world. We have been, Le Guin’s theory proposes, operating under the presumption that the hero is either here or is coming soon, pistols firing, lasers blasting. Are we the hero? Are we waiting for someone else to be?

It has to do with how we understand the history that has come before us and that we are making right now— what historian William C. Anderson calls the focus on the “great men” (and women) that ignores the hundreds and thousands of “rank and file” people. Common people, the folks who did all of the everyday, boring, seemingly mundane actions that all together created huge changes. The thousands of soldiers in WWI who began to refuse to fire on their “enemies” as the war became more and more clearly absurd, and whose small and large mutinies were what actually ended that war, not the politicians whose names we know. The Black women who made the food that became free breakfast for schoolchildren with the Black Panther Party’s survival programs—one of many actions so threatening that the US government declared the Panthers “public enemy number one,” leading to assassinations and more. We know Edgar J. Hoover’s name (the FBI director at the time) and some of us know Eldridge Cleaver’s name, but what about those women, making breakfast each morning? I’m not saying that we need to start memorizing more and more and more names but rather, that we need to know and remember that all of those mean and women existed, that they were a fundamental part of those stories, and that without them, there is no story at all.

Those who voted for Trump desire, as they have been trained by our stories, a hero. Most who voted against Trump also desire a hero. Those who feel disempowered, exhausted, heartbroken, lied to—what would we feel, if we had been brought up on stories with people in them, instead of heroes? With many small threads that came together to weave the tapestry?

“Finally, it's clear,” Le Guin says, “that the Hero does not look well in this bag. He needs a stage or a pedestal or a pinnacle. You put him in a bag and he looks like a rabbit, like a potato.”

It may seem pretty depressing to be a potato, but to me it sounds delightful. Restful. If being the hero means being the one in a position to destroy millions of lives, I would rather be a potato, thank you. If being a potato means I can be one dusty, slightly lumpy part of a collection of dusty, slightly lumpy brethren who collectively achieve some amount of ease or joy or caregiving, then I would rather be a potato.

In the podcast The Left Hand of Le Guin, in an episode discussing “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” David Naimon talks about how in the 1970s, Le Guin told her agent that she didn’t want to write male protagonists anymore, but she also didn’t know how not to write them. And she didn’t publish a book with a female protagonist until 1990, when she returned to the Earthsea universe and wrote Tehanu.

I propose, in the spirit of Le Guin’s essay and also in the spirit of her own continued journey and willingness to keep learning and changing and returning and re-visioning, that we cannot write stories or tell stories—or believe in—heroes anymore.

I say this, with full acknowledgement that I don’t fully know myself exactly how to do that. Le Guin’s essay, which covers much more than the bits I’ve discussed here, has many pointers towards how to do so in fiction, and there’s a rich array of responses to her essay that you can find if you’re interested.

I wrote this for you in a single night, while making dinner for my two children, and I’m sure I’ve made mistakes and left important things out and possibly left you confused at moments.

But I propose that the question itself, the desire itself is a powerful place to begin. Let’s try out traveling together in this carrier bag. It’s cozy here, and there’s plenty of potatoes. Imagine what we might be able to create, together.

With love and rage,

Adrie

P.S. As I am finishing my grad school semester, I’m putting together a writing group for chronically ill/disabled folks, and a writing group for women. Interested? Reply to this and/or stay tuned for more info here.